Dende’s Essay And His Mother’s Lion By Johnson Babalola

My late uncle, Baba Oguns as we called him, told me a story in 1981 that was funny to me at the time.

He told the story of a school essay assignment in his early years at Oyemekun Grammar School, Akure (OGSA). On this day, the no-nonsense English teacher had asked the students to write an essay on “The Lion”. He gave them three days to submit their essays. “Any student whose essay is not well researched will be punished in addition to failing the paper.” He warned. In those days in Nigeria, teachers were mini gods. They were feared and revered. The teachers themselves were dedicated, knowledgeable, focused, punitive and in some cases, unsupportive.

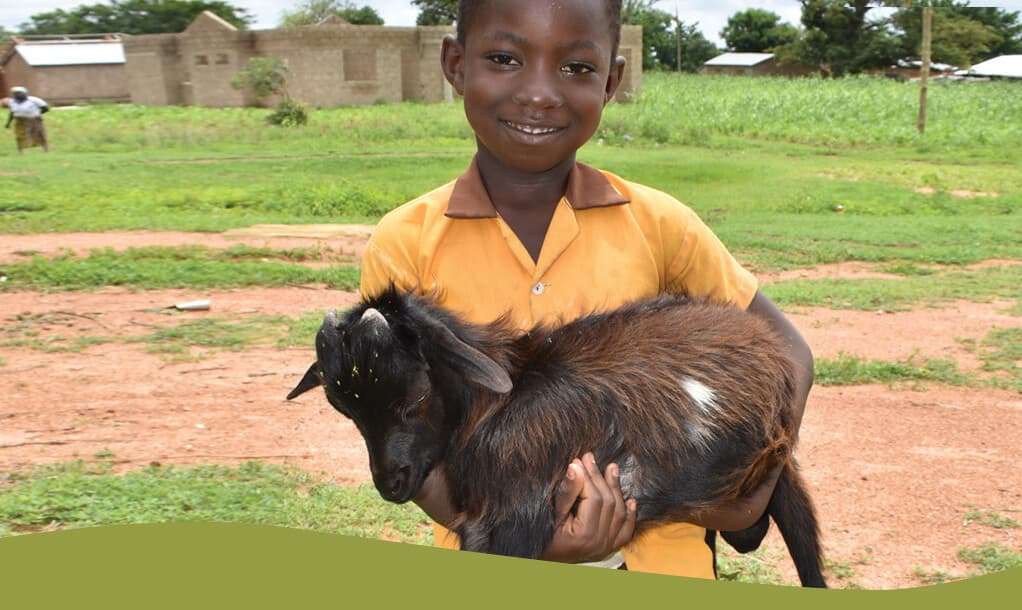

Dende, like many in his class, had never seen a lion. His knowledge of the animal was from the daily folk stories told by his parents, uncles, aunts, and others after supper. He had many images of the animal in his mind. However, his strongest interpretation of what a lion looked like was a goat. He was convinced a goat and a lion belonged to the same family. Dende had no academic mentor. His parents were not educated. He was the first in his family to attend a high school. He was also too afraid to ask his teachers and his classmates for guidance. Rather than do that, he got to work and wrote his essay that partly read:

A lion has two eyes, two ears, four legs, two horns, a nose, a tail, and some hairs on its body. It has different colours. It makes noise when you take its child away. My mother has a lion.

Dende submitted his essay as did the other students. After marking the essays, the teacher announced the marks to the whole class. About seventy five percent of the students including Dende failed. Bola, the student that scored the highest mark was the son of a permanent secretary in a Federal Ministry. He had been to zoos in the USA, UK, and the University of Ibadan multiple times. He had read books on animals and watched animal documentaries on the television. Dende in contrast, came from a village called Ikota. Akure was the first town he ever visited and to him, Akure was akin to London. He had never been to a zoo and had never seen a television in his life. Yet he was asked to compete with the likes of Bola. Without proper guidance and resources, his failure was almost guaranteed.

As I recall this story today, I think differently about the hidden message therein and reality of many. To be poor is a life sentence to failure in most third world countries. Every obstacle is placed in the path of a poor person. He is provided with no tools to succeed. He receives no support to find his path in life. He is asked to write an essay on an imagined trip to London when he has never left his village. He is asked to use the computer to write his high school final exams when he has never seen or used a computer in his life. He is asked to communicate in a foreign language that makes the interpretation of the very thing he is expected to master foreign to him. Yet, he must not complain. When he summons the courage to speak, nobody listens to him because his opinion does not matter. He is a nobody. Despite all these, he is still expected to be upright and do well. He must not steal. He must not lie. He must not misbehave. He must not cut corners. If he does not behave or do well as expected, he gets blamed for his own failure and the failures of us all. He might even get punished. Yet those responsible for his situation in life are rewarded with awards, promotions, honours and a pat in the back for a job well done.

Until the leaders of third world countries realize the importance of education for all; appreciate the need for equality of all; and embrace egalitarianism, the countries will continue to lag far behind others.

There are many Dendes among us. Some will survive and make it through hard work and luck, others will unfortunately not. It is important though that we endeavour to make a positive difference in the life of the Dende we come across, understanding that if he does well, we all do well. If he fails, we are all impacted by his failure.

Johnson Babalola is a Canadian immigration lawyer, writer, storyteller, and story-based management trainer. Follow him on IG @jbdlaw; FB: https://www.facebook.com/jbdlaw and http://www.johnsonbabalola.com/